Cape Cod Bay Should Be Classified As An Outstanding Resource Water

A Way to Halt Holtec: Arguments From My Letters to EOEEA and MassDEP

[Readers, here are my arguments, which I sent today to Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EOEEA) Secretary Rebecca Tepper; Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) Commissioner Bonnie Heiple; and MassDEP’s Director of the Division of Watershed Management Lealdon Langley.

If you wish to make similar points to respectfully request that Cape Cod Bay be designated an Outstanding Resource Water because of its “outstanding socio-economic, recreational, ecological and/or aesthetic values,” you can email Sec. Tepper at env.internet@mass.gov; Commissioner Heiple at Bonnie.Heiple@mass.gov; and Director Langley at Lealdon.Langley@mass.gov.]

Dear Commissioner Heiple,

I hope this letter finds you well. My name is Benjamin Cronin. I grew up and reside in Duxbury, and I write to you to urgently request that the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) classify Cape Cod Bay under Massachusetts anti-degradation standards (found at 314 CMR 4) as an Outstanding Resource Water (described below).

I should note that though I am a member of both the Town of Duxbury Nuclear Advisory Committee and the grassroots Save Our Bay Coalition — formed to oppose the proposed illegal discharge by Holtec of approximately 1.1 million gallons of radioactive wastewater from Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station into Cape Cod Bay — what follows are my own views as an individual citizen.

My own background is as an academic historian who wrote his doctoral dissertation on the preservation of the commons — publicly owned resources of stream and pond, sea, forest, and field, primarily in, but not limited to, Duxbury, Pembroke, and Wareham, especially via Town Meetings, from the 17th,18th, and 19th centuries. The idea of the commons — natural resources that necessarily affected and are affected by all – are of great antiquity at both common law, and prior to that, Roman law. My letter to you today is, indeed, premised upon that long corpus of precedent, though I do note that I am not a lawyer.1

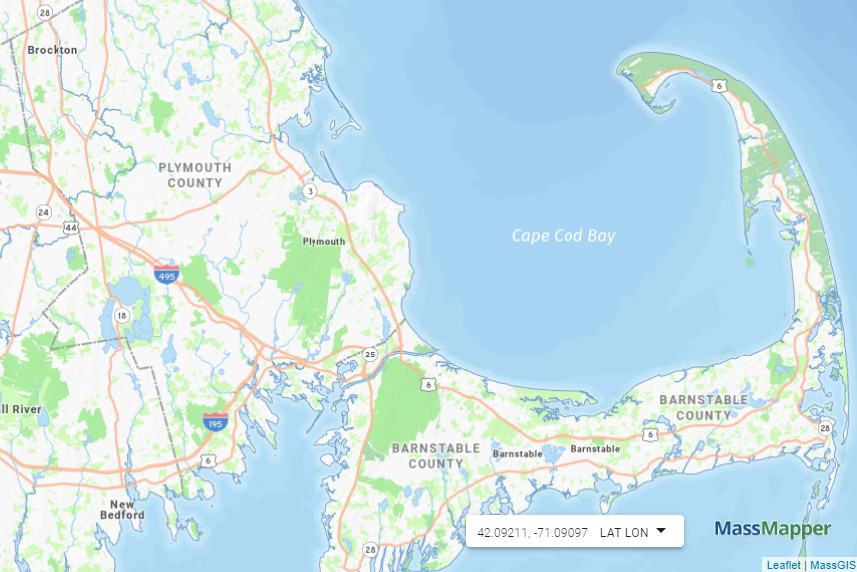

(Cape Cod Bay; credit — MassGIS.)

I. Holtec’s Proposed Discharge Is Illegal

Before turning to the main topic of this letter, the merits and necessity of reclassifying Cape Cod Bay as an Outstanding Resource Water (ORW), I did want to raise one important preliminary point: the proposed discharge is plainly illegal, and therefore ought to be rejected on its face.

Indeed, in the June, 2020 Settlement Agreement between the Massachusetts Attorney General’s office and Holtec, both parties agreed that “Holtec shall comply with all applicable environmental and human-health based standards and regulations of the Commonwealth;” (Settlement Agreement, III (10)(l)). Those standards and regulations include the Massachusetts Ocean Sanctuaries Act (M.G.L. c.132A §§12A-16J, and §18), which defines all of Cape Cod Bay, inclusive of Duxbury, Kingston, and Plymouth Bays, as a protected Ocean Sanctuary (§13(b)); prohibits the “the dumping or discharge of commercial, municipal, domestic or industrial wastes” into any ocean sanctuary (§15(4)); and forbids the Commonwealth from permitting any activities which are prohibited under the Act (§18).

Despite what is sometimes averred, there is no Federal preemption in this instance. For one thing, the Settlement Agreement is a contract, and my understanding is that contracts are not preempted.

Moreover, United States case law supports the contention that there is no preemption. The United States Supreme Court has held on four separate occasions that while Congress granted the field of nuclear safety to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), under the United States Constitution, States retain their legitimate authority to regulate their individual economies, and that states may regulate nuclear matters in that capacity, and indeed, in those capacities not ceded by Congress to the NRC, i.e., those not relating to nuclear safety. The Court ruled that there is only preemption if there is a contradiction between Federal and State laws and regulations. Since there is no Federal law or regulation requiring Holtec to discharge this water — it simply wishes to, for financial reasons — there is no contradiction between Massachusetts and Federal laws and regulations. Precedent therefore impels the conclusion that there is no federal preemption in this instance.2

The proposed discharge is therefore facially illegal and must be rejected as such by relevant Massachusetts departments and agencies.

II. The Urgent Need to Reclassify Cape Cod Bay As An Outstanding Resource Water

(Clark’s Island, in Duxbury Bay, from Saquish Head; both geographical features are part of the Town of Plymouth, politically, though they are located in Duxbury Bay; credit — J. Benjamin Cronin.)

Nevertheless, even were it not illegal on its face, Holtec’s application to MassDEP for a modification to its NPDES (National Pollution Discharge Elimination System) permit fails to meet the anti-degradation standards included in Massachusetts and United States regulations. This discussion is limited to the former.

Presently, the DEP presumes that Cape Cod Bay is designated as High Quality Waters, which would, in my understanding, be subject to a Tier 2 Review standard; however, I can find no designation of it as such at 314 CMR 4.06(5).

Given all of the above, I therefore believe there is urgent need to designate Cape Cod Bay, including its many arms like Duxbury, Kingston and Plymouth Bays, Barnstable and Wellfleet Harbor, and many more, an Outstanding Resource Water, subject to the more robust Tier 21/2 review standard under 314 CMR 4.06(1)(d)(2):

“Outstanding Resource Waters denotes those waters that are designated for protection as Outstanding Resource Waters under 314 CMR 4.04(3). Outstanding Resource Waters are assigned at the discretion of the Department, as appropriate. An application to nominate a waterbody as an Outstanding Resource Water must be submitted in accordance with applicable Department application procedures and requirements.”

Outstanding Resource Waters (ORWs) are defined at 314 CMR 4.02:

“Waters designated for protection in 314 CMR 4.06, which include Class A Public Water Supplies (314 CMR 4.06(1)(d)1) and their tributaries, certain wetlands as specified in 314 CMR 4.06(2), certain surface waters designated in 314 CMR 4.06(6)(b), and other waters as determined by the Department based on their outstanding socio-economic, recreational, ecological and/or aesthetic values.”

All of these are in evidence in Cape Cod Bay.

In socio-economic terms, the Bay is a key resource for the Commonwealth. In 2016, the entire Blue Economy of the region (fishing, recreation and tourism, marine science, transport, and marine infrastructure) was worth approximately $1.4 billion dollars, according to the Cape Cod Blue Economy Foundation; with inflation, that is closer to $1.78 billion today, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Inflation Calculator. The thriving aquaculture industry of Duxbury, Kingston and Plymouth Bays, the lobstermen of Green Harbor and Sandwich, and the many thousands of people engaged in recreational fishing, are significant economic drivers for the region.

The recreational value of the Bay and its arms is likewise evident. In October, 2000 — over 2 decades ago — the Cape Cod Commission estimated the region saw 5.23 million tourists annually; with population growth, that number has surely increased. In 2020, according to the National Park Service, there were over 4 million visitors to just the Cape Cod National Seashore – which touches Cape Cod Bay in Provincetown and Wellfleet, and includes its eastern bounds, Race Point.

Attractions for visitors from near and far, as well as for longtime local inhabitants, include the several Massachusetts State Parks which touch Cape Cod Bay or its arms, including Pilgrim Memorial Park, on Plymouth Harbor; Ellisville Harbor State Park, in South Plymouth; Scussett Beach State Reservation, in Sandwich; and ever so briefly, Nickerson State Park in Brewster. The Myles Standish Monument State Reservation in Duxbury, though the property itself does not touch the Bay, is the dominating feature of a peninsula dividing Duxbury and Kingston Bay.

There are several Areas of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC) that are either in Cape Cod Bay itself, directly touching the Bay, or proximate to the Bay or its arms: Ellisville Harbor ACEC, in Plymouth; Herring River Watershed ACEC, which touches the Cape Cod Canal though not the Bay itself, in Plymouth and Bourne; Sandy Neck Barrier Beach System ACEC, in Sandwich and Barnstable; Inner Cape Cod Bay ACEC, in Brewster, Orleans, and Eastham; and the Wellfleet Harbor ACEC, in Wellfleet and Truro.

New England’s vigorous and enduring commons tradition has, at the level of the several Towns surrounding Cape Cod Bay, likewise been a factor in producing a number of public or quasi-public open spaces either adjacent to the Bay and its arms and tributaries, or directly abutting it. The following are owned either by individual Towns, or by conservation non-profits and devoted to their preservation and public enjoyment; this list is a sampling, and non-exhaustive; the owners are in parentheses: in Marshfield, Wharf Creek-Estes Woods (Town of Marshfield) and adjacent Daniel Webster Wildlife Sanctuary (Massachusetts Audubon Society), on Green Harbor River, which empties into the Bay; in Duxbury, Common Island (Town of Duxbury) on Duxbury Bay, and Duxbury Beach (Duxbury Beach Reservation), dividing Duxbury Bay from Cape Cod Bay; in Kingston, Grays Beach Park (Town of Kingston), on Kingston Bay; in Plymouth, Holmes Field (The Trustees of Reservations), and adjacent Nelson Memorial Park (Town of Plymouth), above the mouth of Plymouth Harbor; in Bourne, The Strand (Town of Bourne), on Cape Cod Bay; in Sandwich, Town Neck Beach (Town of Sandwich), on Cape Cod Bay; in Barnstable, Great Marshes Conservation Area (Town of Barnstable), on Barnstable Harbor; in Yarmouth, Lonetree Creek Conservation Area (Town of Yarmouth), at the mouth of Barnstable Harbor; in Dennis, The George H. Chapin Memorial Beach (Town of Dennis), on Cape Cod Bay; Saint’s Landing (Town of Brewster), in Brewster, on Cape Cod Bay; Skaket Beach (Town of Orleans), on Cape Cod Bay in Orleans; Hatch Beach (Town of Eastham), on Cape Cod Bay, in Eastham; in Wellfleet, Mayo Beach, on We (Town of Wellfleet); Fisher Beach (Town of Truro), separating Pamet Harbor from Cape Cod Bay, and across the harbor, Little Island Meadow (Truro Conservation Trust); and in Provincetown, MacMillan Wharf (Town of Provincetown), on Provincetown Harbor.

In ecological terms, the bay is already threatened. Recent years have seen the appearance of hypoxia in the southern portion of the bay, while algal blooms and eelgrass die-off affect waters throughout the bay, and indeed, the entire region. The threats from nitrogen runoff are so severe that upcoming changes to Title V (septic system) regulations will likely affect the entirety of Cape Cod, and significant portions of southern Plymouth County. It is preeminently not the time to add radiological pollutants to the litany of ecological worries with which the Bay must contend.

In terms of Cape Cod Bay’s aesthetic value, it has provided a source of solace and serenity, as well as been the subject of depiction and expression, for generations of writers, painters, and other artists. The artistic-theatrical colony that began at Provincetown about a century ago is but one example; Henry David Thoreau’s writings on the region likewise form an important part of the cultural heritage of the Commonwealth and the nation. It is by any reasonable understanding aesthetically rare and valuable.

For all of the foregoing reasons, I believe Cape Cod Bay, including its several arms, should be classified as an Outstanding Resource Water (ORW), subject to a Tier 2 ½ standard of review, and I most respectfully request that your office designate them as such.

Thank you for your time and consideration.

Sincerely,

J. Benjamin Cronin, Ph.D

Duxbury, Massachusetts

The public nature of the ocean is of great antiquity at law, and not only in the Common Law, but also the Roman Law before it. My understanding is that the primary authority at Common Law on this subject is the 17th century English jurist Lord Chief Justice Matthew Hale, author of the treatise De Jure Maris (“Of the Law of The Sea”).

U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Horace Gray, writing for the Court, provides a useful summary of Lord Hale’s summation of Common Law in Shively v. Bowlby, 152 U.S. 1 (1894):

“By the common law, both the title and the dominion of the sea, and of rivers and arms of the sea, where the tide ebbs and flows, and of all the lands below high water mark, within the jurisdiction of the Crown of England, are in the King. Such waters, and the lands which they cover, either at all times or at least when the tide is in, are incapable of ordinary and private occupation, cultivation, and improvement, and their natural and primary uses are public in their nature, for highways of navigation and commerce, domestic and foreign, and for the purpose of fishing by all the King's subjects. Therefore the title, jus privatum, in such lands, as of waste and unoccupied lands, belongs to the King, as the sovereign, and the dominion thereof, jus publicum, is vested in him as the representative of the nation and for the public benefit.” (Page 152 U.S. 11)

The Crown, of course, as the guardian of the sea in public trust, has been replaced in our situation since the American Revolution with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the United States.

Lord Hale is worth quoting here, as well, from De Jure Maris, Pars Prima, Cap. IV:

“The right of fishing in this sea and the creeks and armes thereof is originally lodged in the crown….But though the king is the owner of this great wast, and as a consequent of his propriety hath the primary right of fishing in the sea and the creekes and armes thereof; yet the common people of England have regularly a liberty of fishing in the sea and the creekes and armes thereof, as a publick common of piscary, and may not without injury to their right be restrained of it, unless in such places creeks or navigable rivers, where either the king or some particular subject hath gained a propriety exclusive of the common liberty.”

I would suggest that this is precisely one of the issues brought forth by this public controversy: Holtec is essentially seeking to exercise, contrary to law, “a propriety exclusive of the common liberty” – a propriety which they simply do not possess.

Indeed, the roots of these common liberties reach deep into the Common Law, being formally codified in the 1217 Charter of the Forests, a companion document to Magna Carta. In the Charter of the Forests, the Crown declares universal rights with respect to its free subjects’ common access to Royal Forests (in the sense used here, Royal Forests were simply owned, enclosed land used for hunting by the Crown; many were forest ecosystems, but many were not, with moorland being present as well, for instance), in which the Crown declares: “These liberties concerning the forests we have granted to everybody….” (1217 Charter of the Forest, 17; transl. Appears in Harry Rothwell (ed.), English Historical Documents, Vol. 3, 1189-1327 (London, Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1975), No. 24, at pp. 337-40; via Dr. John Langton and Dr. Graham Jones: http://info.sjc.ox.ac.uk/forests/Carta.htm)

The 6th century Code of Justinian, a summation and codification of centuries of Roman law, acknowledges the public ownership and character of the sea:

“By the law of nature these things are common to mankind---the air, running water, the sea, and consequently the shores of the sea. No one, therefore, is forbidden to approach the seashore, provided that he respects habitationes, monuments, and buildings which are not, like the sea, subject only to the law of nations.” (The Code of Justinian, Book II (I)(1), https://thelatinlibrary.com/law/institutes.html)

This, in my understanding, is the original fount of the public trust doctrine with respect to our oceanic commons.

See Pacific Gas & Electric Co. v. State Energy Resources Conservation & Development Commission, 461 U.S. 190 (1983); English v. General Electric Co., 496 U.S. 72 (1990); Silkwood v. Kerr-McGee Corp., 464 U.S. 238 (1984); Virginia Uranium, Inc. v. Warren, 587 U.S. ___ (2019).

Writing for the unanimous Court in English v. General Electric, Justice Harry Blackmun noted the logically absurd conclusions towards which the arguments from the nuclear industry drive: “In addressing this issue, we must bear in mind that not every state law that in some remote way may affect the nuclear safety decisions made by those who build and run nuclear facilities can be said to fall within the preempted field. We have no doubt, for instance, that the application of state minimum wage and child labor laws to employees at nuclear facilities would not be preempted, even though these laws could be said to affect tangentially some of the resource allocation decisions that might have a bearing on radiological safety.” (Page 496 U. S. 85)

You are the bomb! Beautifully said and as far as I'm concerned, an incontrovertible argument.