Bridgewater's Lake Nippenicket Threatened By Developer

Claremont Proposes Hundreds of New Units Next To Great Pond at the Heart of the Hockomock Swamp, Largest Freshwater Wetland in Massachusetts

[ Readers, comments on the project (No. 16558) are due to MEPA by Monday, Jan. 23rd, and can be submitted directly at: https://eeaonline.eea.state.ma.us/EEA/PublicComment/UI/searchcomment, or via email to: purvi.patel@mass.gov. - Ed. ]

(BRIDGEWATER) — Lake Nippenicket, a 354-acre Great Pond1 in Bridgewater that serves as a source for both the Town River and the Taunton River, supports a productive fishery, and sits in the heart of the vast Hockomock Swamp — the largest freshwater wetland in Massachusetts — is threatened by a proposed 68.2 acre development on its shores by the Claremont Companies, a southeastern Massachusetts real estate developer.

( A view of Lake Nippenicket; photo credit — Jeremy Gillespie. )

The proposed development, on a partially developed site off of Route 104 in Bridgewater owned and used as a headquarters by Claremont, would sit directly proximate to the southern shore of the environmentally valuable and ecologically sensitive pond — locally nicknamed “The Nip.”

The proposal, according to a Dec. 15, 2022, Draft Environmental Impact Report (DEIR) submitted by Epsilon Associates, a Maynard engineering firm, on behalf of Claremont to the Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act Office (MEPA), includes a 225-unit, 4-story, 55+ residential structure; a 150-unit, 5 story assisted living facility; a 4 story, 160 unit condominium; a 4 story, 106 unit hotel; a cafe; and a 179-seat restaurant directly on Lake Nippenicket.

Opponents Argue Development Threatens Critical Water Supply, Ecosystems

Grassroots opposition is presently gathering, including the Lake Nippenicket Action Focus Team ( lnaft.org). Critics argue that the site of the proposed development is located in an Area of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC), the Hockomock Swamp (on which see more below), and that Lake Nippenicket is the headwaters of Bridgewater’s Town River, which flows into the Taunton River, a National and Scenic River that drains 562 square miles across Southeastern Massachusetts. Approximately 25 acres of forest would be destroyed, removing both a valuable watershed filter and a critical carbon sink, reducing the ability of the Town of Bridgewater — and the entire Commonwealth —to mitigate and ameliorate the effects of climate change. Indeed, such a proposal is the very antithesis of climate resilience, which has been one of Gov. Healey’s highest priority policy goals and watchwords thus far in her young Administration.

The proposal intrudes upon the 100-foot buffer zone areas of wetland resource areas, and poses a threat to the biodiversity of Massachusetts, as the site is habitat for the Eastern Box Turtle, a species of special concern. The site is moreover in a Massachusetts Dept. of Environmental Protection (MADEP) Zone II Wellhead Protection Area for the Town of Raynham.2

There is likewise significant concern regarding the effect on Native archaeological sites that may be affected.

The developer, meanwhile, is disputing the classification of three perennial streams on the property, although they are clearly marked as such on the USGS Geological Survey Topographical Maps of the area, say critics.

Claremont: A Pattern of Attempting To Use Public Goods for Private Gain

Context is important here: Claremont’s invasions of the watery commons of the Commonwealth — for their own, private profit — are not limited to Bridgewater. The same developer, after all, under its Claremont Plymouth limited liability corporation, is engaged in a project at Colony Place in West Plymouth that abutters and concerned Plymoutheans, citing multiple reports from engineers commissioned by the Town, argue poses a severe threat to Plymouth and her neighbors’ water supply, the Plymouth-Carver Sole Source Aquifer.

( The shores of “The Nip”; photo credit — Jeremy Gillespie.)

Lake Nippenicket is extremely shallow, with an average depth of just three feet, and a maximum depth of six feet, according to the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (MassWildlife). Fish species, according to MassWildlife, include “yellow perch, pumpkinseed, bluegill, largemouth bass, white perch, black crappie, chain pickerel, brown bullhead, golden shiner and American eel. A large number of quality sized largemouth bass up to 5.5 pounds were captured during the 1990 survey. White sucker and alewife (searun) were captured in the 1978 survey.”3

The shallowness of the lake is one reason the runoff that would occur from such a development is such a concern. Nor is this Claremont’s first bite at this particular apple; a similar proposal in 2020 by Claremont to build a restaurant on Lake Nippenicket was strenuously opposed by the Taunton River Watershed Alliance (TRWA), an environmental advocacy group headquartered in Taunton. In that case, Claremont was asking Bridgewater to essentially ignore its own zoning bylaws so that it could build its restaurant directly on the Lake.

“TRWA opposes this request because the proposed construction would harm the water quality in Lake Nippenicket and the ecological communities that inhabit the site and surrounding area. These impacts would occur as a result of earth removal and other work during construction, the rendering of a large portion of the property to impermeable surface, and the discharge of polluted stormwater runoff after the project is completed,” wrote TRWA President Priscilla A. Chapman, in a March 14, 2020, letter to Patrick Driscoll, Chair of the Bridgewater Planning Board.

"This project sets a dangerous precedent for other future potential developments that may be planned within sensitive areas within the Town,” wrote Chapman, who noted that the Town’s 2002 Master Plan calls for the preservation of the shores of Lake Nippenicket, the largest body of water in Bridgewater.

The Hockomock Swamp, said Ms. Chapman, “is home to at least 13 species listed as endangered, threatened or of special concern by the Massachusetts Natural Heritage Program, including the blue spotted salamander, (Ambystoma laterale), listed as ‘threatened.’”

The Hockomock Swamp: Natural and Human History

The Hockomock Swamp is a vast complex of swamps, marshes, rivers, ponds, and other ecosystems that, at nearly 17,000 acres, is the largest freshwater wetland in Massachusetts; Lake Nippenicket is part of this complex. It serves as a critical zone of recharge for the region’s aquifers, and the source of many rivers and streams, including the Taunton River, which, flowing for 37 miles through ten towns, is a critical water resource for its entire 562 square mile basin, from Halifax to Fall River, and from just a few miles west of Plymouth Bay, in the east, all the way to Plainville, in the west.

( The heart of The Hockomock; Lake Nippenicket is at the lower center, immediately northwest of the junction of I-495 with Mass. Route 24; photo credit — Google Earth. )

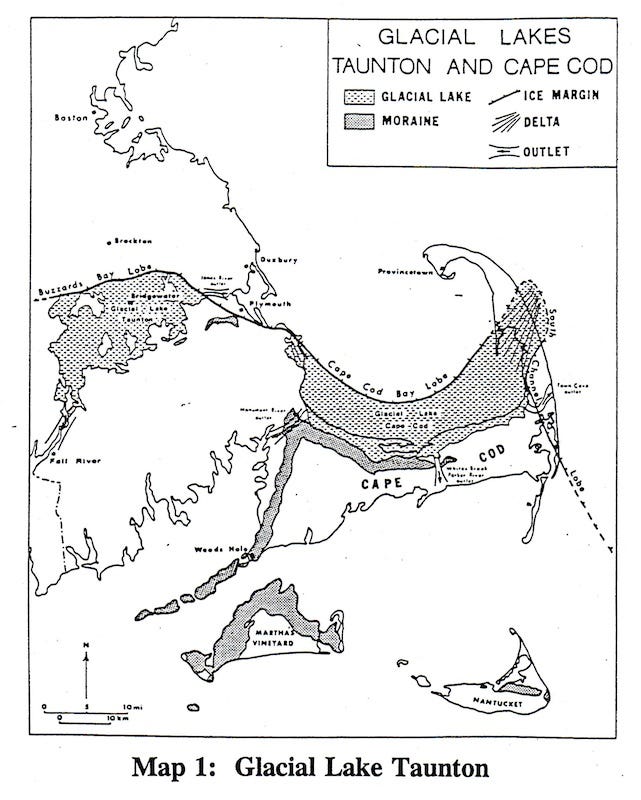

The Hockomock sits in the basin of glacial Lake Taunton, which was formed in the long process of glacial retreat; the impermeable soils of the lake bottom form the geological core of the vast wetland.

( Southeastern Mass. in the age of glacial retreat; Glacial Lake Taunton surrounds what is today Bridgewater; photo credit — G.J. Larson, Larson, “Non-synchronous retreat of ice lobes from southeastern Massachusetts,” 1982. )

The Hockomock, including Lake Nippenicket, is a mysterious, wild, and beautiful landscape, with a rich natural and human history. As one of the few remaining watery wildernesses of this size in southern New England, it serves as a refugium for flora and fauna that are threatened by the relentless attempts by development interests to realize private profits through the enclosure of public goods, like water. Mass Audubon notes that in addition to serving as a home to several important bird populations, the wetland is important in a broader sense: “Atlantic White Cedar swamps, especially of large acreages, are globally rare and uncommon in southeastern Massachusetts. This large swamp undoubtedly has a good population of mammals, including mink, fishers, and bobcats,” says Mass Audubon.4

( Below: the larger Hockomock Swamp region, with Lake Nippenicket at the bottom of the image, to the west of the red line that indicates Mass. Rt. 24; photo credit — Mass. Audubon. )

( A more detailed map of the area of the proposed project; photo credit — Mass. Department of Conservation and Recreation. )

The human history of the Hockomock is likewise of critical importance in the life of our region. Evidence of human habitation in the area extends seven thousand years before the present on the shores of Lake Nippenicket, and a preserved, Native dugout canoe was unearthed in the swamp in 1970. Atlantic White Cedar Swamps such as the Hockomock were used as places of refuge by Native people, including as fortresses in time of war — the impenetrable wetlands offered protection against invaders, particularly Europeans who had no knowledge or experience of their ecology. One of the largest battles of King Philip’s War, the Bridgewater Swamp Fight, took place between English and Native forces in August, 1676, and was a brutal affair on both sides.

( The Southern Theater of King Philip’s War, including the Battle of Bridgewater Swamp in August, 1676; photo credit — Richard W. Wilkie and Jack Tager, in Historical Atlas of Massachusetts. )

The memory of the immensely bloody (as a proportion of population on both sides) fighting in the swamps of the Hockomock, I would argue, lodged itself in the historical consciousness of the region; in particular, I would argue that it is expressed today in the folk mythology surrounding “The Bridgewater Triangle” and what some suggest is heightened supernatural activity in the area, including stories of demon dogs, will o’ the wisps in the haunted swamp, and disappearing hitchhikers. Putting aside those claims, it is clear that the great violence that occurred in the swamp nearly 350 years ago still inheres in our collective memory, even if in attenuated, subconscious form, today.

Precisely because it was not useful from the point of view of either colonial agriculture or the Industrial Revolution, local people continued to use the Hockomock as a vast commons in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, and continuing today, fishing, hunting, trapping, and gathering in its remote recesses.

Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, amid the burgeoning environmental movement, efforts were made to inform the public of their magnificent natural commons, and the need to guard them for posterity. Local conservationists, including the authors of the excellent 1968 pamphlet, Hockomock: Wonder Wetland — still the one of the finest sources of information on the Hockomock — made the case, successfully, that the wetland is a critical natural resource that belongs to us all.5 Ultimately, citizens and their government were able to extend legal protections to the Hockomock, which was designated as an Area of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC) in February, 1990.

Claremont’s Proposal Violates The Relevant Massachusetts Regulations

Which brings us to the current proposal by Claremont to add new development to the Hockomock Swamp ACEC. The entire proposal stands in stark contradiction to the language of the Massachusetts regulations governing Areas of Critical Environmental Concern, specifically the language at 301 CMR 12.11 (1)(b) and (c), which states that “all EOEEA agencies shall take action, administer programs, and revise regulations in order to,” inter alia, “preserve, restore, or enhance the resources of the ACEC,” and “ensure that activities in or impacting on the area are carried out so as to minimize adverse effects on: 1. marine and aquatic productivity; 2. surface and groundwater quality or quantity; 3. habitat values and biodiversity; 4. storm damage prevention or flood control; 5. historic and archeological resources; 6. scenic and recreational resources; and 7. other natural resource values of the area.”

I would suggest that the proposal for a 68.2 acre development on the parcel in question does in fact, impose adverse effects on every one of those enumerated categories. Indeed, the proposal to construct hundreds of new units in an ACEC is wildly inappropriate. This is most properly understood as the creation of a small village in one of the areas of the Commonwealth that has, under the law, an elevated degree of environmental protection and consideration. It is precisely what the ACEC designation was intended to prevent.

The relevant Massachusetts regulatory authorities therefore should reject this proposal, and continue the work of past decades in preserving our treasured watery wilderness at the heart of Southeastern Massachusetts.

Comments on the project (No. 16558) are due to MEPA by Monday, Jan. 23rd, and can be submitted directly at:

https://eeaonline.eea.state.ma.us/EEA/PublicComment/UI/searchcomment

or via email to: purvi.patel@mass.gov.

( A Great Pond, Common to all — Lake Nippenicket: a place worth keeping; photo credit — Jeremy Gillespie. )

Under the laws of Massachusetts and other New England states, a freshwater pond that is more than ten acres is a Great Pond, that is open commonly for fishing and navigation, and, unless it is a reservoir, must allow public access; in Massachusetts as well as several of her neighbors, Great Ponds are defined both by statute and at common law.

There is a disturbing tendency in our region for developments in one Town to pose a threat to the water sources of another, sometimes despite, and in apparent contravention of, explicit legal protection afforded to to these water sources; see, e.g., the proposed Rountree car dealership in Plymouth that would sit directly atop land that is supposed to be protected in perpetuity in order to safeguard Kingston’s water supply.

See https://www.mass.gov/doc/dfwnippepdf/download.

https://www.massaudubon.org/our-conservation-work/wildlife-research-conservation/bird-conservation-monitoring/massachusetts-important-bird-areas-iba/iba-sites/hockomock-swamp.

https://www.bridgewaterpubliclibrary.org/sites/bridgewaterpubliclibrary.org/files/attachments/HockomockWonderWetland-compressed.pdf

Great article. I've recently subscribed to The Plymouth County Observer ( will have to cheack and make sure it was a paid subscription) and am happy that information, as has been discussed here, is getting out to the general public. Dr. Cronin, will you be holding any public speaking engagements with possible outdoor rallies calling for the protection of S.E. Mass wetland areas. Seems groups/companies like Claremont are willing to destroy environmentally sensitive areas for "30 pieces of silver". No moral character. Bill Duggan

These Glacial lakes are very sensitive to change, especially development & pollution within their watershed. These are not artificially constructed "highland" lakes as you see across the the southeast and mid-south, which are deep and very well flushed. Those artificial lakes can handle much more disturbances within their watersheds than these shallow & fragile natural ecosystems. The 100 ft buffer is a joke, if Massachusetts really wants to protect it's rare glacial lakes, rivers and their surrounding habitat, they will need to put laws into place that extends this buffer to 1000 feet in which no future development or disturbances would be allowed to occur.